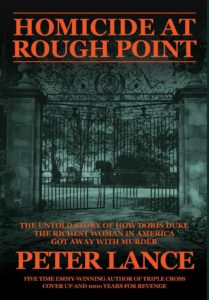

Homicide at Rough Point is a sort of investigative piece into the 1966 Newport death of Hollywood up-and-comer Eduardo Tirella under an automobile driven by the wealthy heiress, Doris Duke. It is an expansion on his 2020 Vanity Fair article “Did Billionaire Tobacco Heiress Doris Duke Get Away With Murder?” The author, Peter Lance, a Newport native, began his journalism career at the Newport Daily News in the year following Eduardo’s death. He has won the News and Documentary Emmy Award five times, and received the Robert F. Kennedy Journalism Award in 1973. He received a B.A. from Northeastern University in 1971, and M.S. from the Columbia Graduate School of Journalism in 1972, and a J.D. from Fordham University School of Law in 1978. He worked for Ralph Nader’s Center for the Study of Responsive Law as one of “Nader’s Raiders” from 1969-72, has worked for WNET, WABC, Nightline, World News Tonight, and ABC News. He has written several investigative books, including 1000 Years for Revenge (2003), Cover-up (2004), Triple Cross (2006), and Deal with the Devil (2013).

Homicide at Rough Point is a “sort of” investigative piece because, as a Newport native, Lance uses the book to reminisce a good deal about his own experiences growing up there and to tell tales about the city’s history and the lives of many of its famous and infamous residents. As a Newporter in my own right, tracing my family history there back several generations, and being a relative of the first patrol officer on the scene of Eduardo’s death, I was entertained by this aspect of the book. I grew up on stories about Duke’s “accident” and had, based on how these stories were told, assumed that she had indeed gotten away with murder.

No one can fault Peter Lance for the amount of evidence that he scared up in relationship to this case, nor for the amount of time he spent doing interviews, and hunting down missing documents. He certainly seems to have brought his investigative training to bear upon the incident of Eduardo’s death and is convinced that Duke murdered Eduardo out of spite when he attempted to extract himself from her employ in order to take advantage of opening doors in Hollywood.

Having read the book, however, Lance, certainly without intending to do so, fed my doubts of Duke’s guilt more than he stoked my convictions of her guilt. Were I in a jury box in a court of law, and this book was the full testimony against Duke, I would vote, “Not Guilty!” Two people know what happened that night. One died. One used her considerable influence to protect herself. Maybe she murdered him, maybe she didn’t, but reasonable doubt continues to exist after Lance’s book, not in small part due to his unprofessional manner of presenting it.

As a whole, Homicide at Rough Point is a poorly conceived work that reveals much more about the author, himself, than it does about the intentions of Doris Duke when Eduardo Tirella perished beneath the wheels of her rented Polara Station wagon. Lance seems to suffer from Trump derangement syndrome, a common ailment of those with his undisguised political bias and its present corresponding societal commitments. He despises the wealth of those who, through their own ingenuity, built the modern world, but celebrates the lives of morally challenged and equally disturbed celebrities and Democrats. Duke’s immorality is cause for scorn, but Roman Polanski’s passes without comment. Lance is plainly star struck with wanton figures like Richard Burton, JFK, and their wives, not to mention the victim himself, whom Lance casts in the role of unrecognized saint. His ignorance of basic economics is plain, as is his own massive ego. Much of the book seems to have no other purpose than to convince you how awesome he is. He sees himself as a modern day Woodward and Bernstein, making the comparison himself. Perhaps his other books bear this out, but not Homicide at Rough Point, where his self-admiration annoyed me more than a little. Here, Lance demonstrates a libelous recklessness in his accusations. He proves unable to imagine any explanation for people’s behavior other than his own conspiracy theories. As I read, I felt like a weary defense attorney, head in hands, saying, “Objection! Conjecture. Objection! Argumentative! Objection! Assumes facts not in evidence! Objection! Lack of foundation! Objection! Irrelevant! Objection! Unqualified opinion! Objection! Leading the Witness! Objection! Unfair prejudice! Objection! Improper character witness! Objection! Misleading! Objection! Hearsay!”

What is obvious in the book is that Lance despises Doris Duke and seeks every occasion to libel her, mining here entire life for points of attack, giving the worst imaginable interpretation of her actions at every turn. He also demonstrates a penchant for rumors and innuendo. He goes far beyond the evidence relevant to the case, and instead engulfs the evidence in a fog of conjecture and irrelevant side-bars designed to convict the woman, doctors, lawyers, and police on emotional grounds alone—“She was a rotten person, so she plainly paid everyone off to cover up her obvious murder of Mr. Tirella.”

The book’s problem isn’t that Lance speculates on whether or not Doris Duke intentionally ran over Eduardo. He provides some new evidence to consider and worked hard to untangle the mess surrounding the weak investigation. So kudos on that. It is that he confuses his often malevolent speculation as evidence.

Lance puts forth his inability to imagine how anyone could mistake the gas for the break and freeze out of panic as evidence that it could not have happened. Yet, I have witnessed exactly this with potentially identical outcomes. He can’t imagine how Eduardo, on the car’s hood, could end up on the road in front of the car unless Doris Duke braked to propel him there. He never once considers the physics involved in smashing through large wrought iron gates. If Eduardo was on the hood, which Lance shows we might reasonably assume he was, in contradiction of the police report, would not the resistance of the gates to the car have propelled him forward through the existing or even opening gap? Cars have a way of slowing suddenly and behaving oddly when encountering resisting objects. Might not the car’s entanglement with the gate have affected much on its pell-mell journey into the tree across the road, tire’s catching or else slipping at points for various reasons? In spite of the fact that the car was new to her, Lance scoffs at the idea that Duke could have been confused by it. He grinds away at small details considered in calm after the fact, and cannot even entertain the possibility that trauma, grief, and shock might affect total recall. And while we are at it, I think we can safely assert that decades might alter the recall of after-the-fact witnesses.

In my personally experienced event, the van shot backwards, leaving different sorts of marks as road tar, gave way to grass and dirt, as curbs, mailboxes, and bushes manipulated the vehicle’s behavior in unexpected ways. My panicked driver only took her foot off the gas some 5-10 seconds after the van could go no further, hung up on debris as it was, both roaring and lurching for more.

Lance cannot imagine any other reason for Doris’ behavior after the fact, other than concealing murder. I, however, cannot imagine that any person would fail to use what influence and power they had to protect themselves in such a situation whether it was on purpose or accidental. Only a fool trusts themselves into the hands of the police, courts, and prosecutors. In terms of her use of money, i.e. her reluctance to settle with Eduardo’s family, one can only imagine the psychological impact of inheriting so much so young and recognizing quickly how manipulative others can be who want to take what you have.

The question is even bigger than this, however. Lance’s propensity for libelous accusation blackens the reputations of many whose actions might have perfectly innocent motives behind them. What people see and do when encountering such a scene and hearing various testimonies from weeping women and from people they know personally and professionally is quite a bit different from what a highly biased journalist imagines they should have done looking back over several decades. The investigation was sloppy, sure, but this does not mean that those involved were criminal in their intent. Lance’s failure to even consider alternatives manifests either a weakness of imagination or the blindness of prejudice. I found his “proof” of guilt for the surrounding players feeble at best and often verging on being downright unscrupulous.

Now, as for the case itself, one “new” witness has come forward after nearly 56 years of silence to back up Lance’s interpretation of the initial event… after reading the book. Bob Walker, a paper boy in the area of Rough Point back in 1966, claims to have heard the sounds of the car crash and insists that his recollection of those sounds backs up Lance’s “hit Eduardo with car, smash through gate, brake to propel Eduardo off the hood, run over Eduardo and smash into tree.” Walker offers explanations for his complete 56 year silence, but there are more than a few reasons to question the legitimacy of his claims. We have defense attorneys for a reason.

If the issues with this book where merely Doris Duke’s guilt or innocence in this matter, this testimony—though questionable after so many years and highly interpretive given his actual proximity to the event—might salvage its value, but the problems with Lance’s book only begin with his interpretation of the actual crash. Lance’s presentation becomes more disreputable as his circles of connection span outward.

In the end, I feel that the tabloid quality of Homicide at Rough Point should have been beneath a legally trained journalist. Unfortunately, this is exactly what I have come to expect from journalists, especially those like Nader’s Raiders. Too often, journalists’ activist tendencies undercut their trustworthiness as journalists.