I am not an art historian, but as I understand the matter, it was not uncommon for great painters of old to put themselves into Biblical scenes as either the bad guys or awed witnesses.

When Good Painters Go Bad

Caravaggio puts his own face on the severed head of Goliath.[1]

Michaelangelo puts his visage onto both a flayed skin of a Christian martyr and as an excited witness of resurrection in his depiction of the Last Judgment.[2]

Albrecht Dürer makes himself a humble witness in the background of the Magi’s adoration of Christ.[3]

El Greco paints himself as humble witness to resurrection glory.[4]

Of course we must not forget the granddaddy of them all— Rembrandt. He shows up as a frightened disciple in a storm,[5] as the prodigal son,[6] one of those crucifying Christ,[7] a witness to the stoning of Stephen,[8] and near the end of his life, as an aged and weary Apostle Paul, the chief of sinners, won to Christ’s service.[9]

Prophetic Art

During my first Master’s degree, I worked for the University in the facilities department. Our job was anything that wasn’t someone else’s job. When the University put on art displays, we would often be involved in the set up.

Once a heavy wrought iron art piece was given to the University in a ceremony. The artist claimed in public to have made it to honor the seven astronauts killed on the challenger. It was five men and two women taken up in a whirlwind to heaven. While three of us carried it to its new home on a stand in the library, we noticed a tiny date etched into the iron base—1982. The challenger was destroyed in 1986. When I mentioned this little factoid to our school president, a funny man, he said, “Wow! Prophetic art! That’s awesome.” Then walked away quickly.

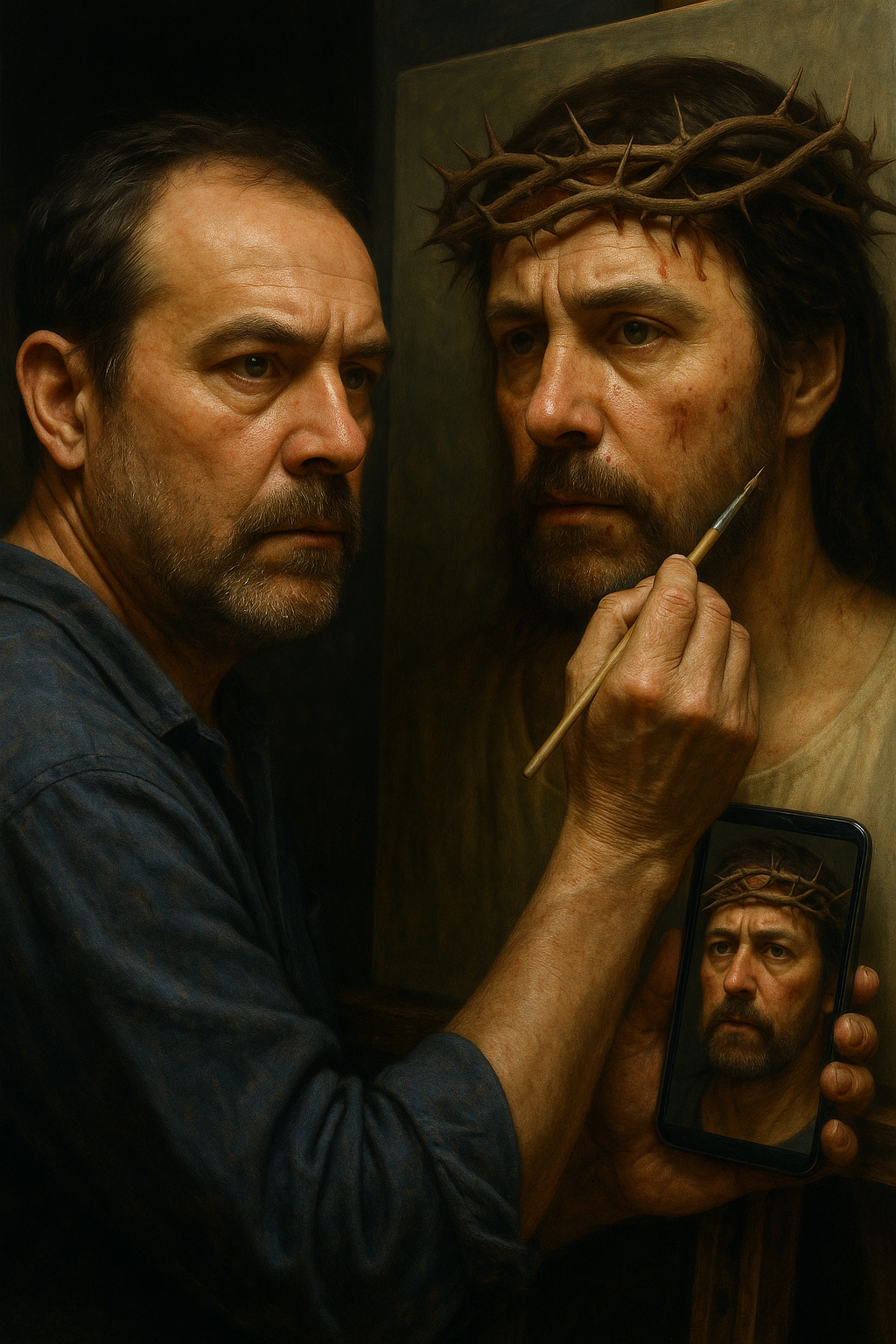

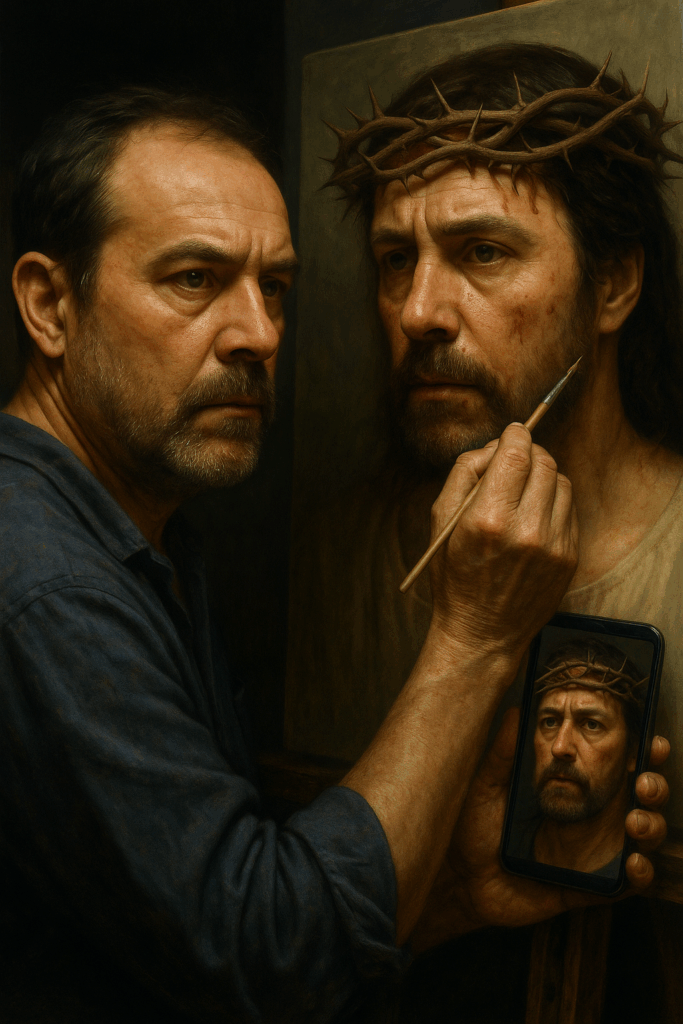

When Egomaniacal Painters Go “Good”

The real kicker for me, was when we hosted a pencil artist with a big display. His work was amazing… photo real in black and white. His entire show was dedicated to the passion week of Christ.

Interestingly enough, he consistently portrayed Jesus in every piece as a pudgy, fifty-something, white guy. I didn’t make too much of it until I met the artist, a pudgy, fifty-something, white guy. I was astonished. Paint yourself as the prodigal son… fine, fair. Paint yourself as Judas, again, fitting. But painting yourself as Jesus? I was so shocked, I exclaimed (yes, exclaimed is the right word) “You painted yourself as Jesus!!!” The artist gave an affected drawl of bored confession, that sounded like Kathrine Hepburn’s would-be fraternal twin, “Well, they were very personal to me, Brother.”

Yeah, That’s a Thing Now

Apparently, it became a thing to turn away from the “Penitential model” employed by Rembrandt and the others, to a self-projection as Christ.

Gauguin, for example, makes himself the anguished Christ in “Christ in the Garden of Olives” (1889)[10] because he was rejected by the Paris Art world. In his own letters, he seems to have made art, and his in particular, a new religion of the self, with him as savior, and the art world as the divine on earth.[11]

James Ensor does so the same year in Christ’s Entry into Brussels,[12] and the wanton Frida Kahlo comes close in her painting Self-portrait with Thorn Necklace and Hummingbird.[13]

When Bad People Paint Themselves Good

A modern equivalent of this is evoked by “Progressive” “Christians” who are like the cereal Grape Nuts… ain’t grapes… ain’t nuts. These have recast themselves as the true exemplars of Christ, painting their own diseased support for humanistic acts of debauchery as walking out the message of Jesus in the modern world.

Jesus you see, say they, would have supported homosexuality, fornication, adultery, abortion. He would have rejoiced in the wanton pursuit of self-actualization in trans ideology as sharing in the creative work of God. He would have been a socialist voting for totalitarian government, hated Western Civilization, and supported the violent overthrow of oppressors for their micro-aggressions. The suffering of “undocumented” immigrants, and minority groups, and women would be seen as reflections of his suffering before those intolerable religious people and their book of laws.

A Biblical Context For the Discussion

When Paul said, “…in my flesh I am filling up what is lacking in Christ’s afflictions for the sake of his body, that is, the church,” (Colossians 1:24 (ESV)) and “That I may know him and the power of his resurrection, and may share his sufferings, becoming like him in his death.” (Philippians 3:10), I don’t think he meant claiming oneself as a Christ figure when every aspect of your life is a violent act of spitting in the face of Christ. It is to take up the Lord’s name in vain… a dark sin.

Paul called himself the chief of sinners. Our response should not be… “Wow! Paul must have been a real mess.” It should be, “Me Too!” Now that’s a Me Too Movement I can really get behind.

When Peter came to his own cross, he who once denied the Lord, felt unworthy to die in the same way. He was instrumental in building the church of Christ and lived a life of sometimes tainted service, but definitely accomplished more than you or I could imagine achieving… but still, he felt unworthy. He asked them to turn the cross upside down.

Oh, Yeah! Well, What About Jesus Himself?

Jesus Himself warned us, “So you also, when you have done all that you were commanded, say, ‘We are unworthy servants; we have only done what was our duty.’” (Luke 17:10 (ESV))

We may defend our actions as imitations of Jesus. We may interpret our unjust suffering as a natural result of serving Christ in a world that hates Him. But we must never paint ourselves as Jesus.

Remember this when you read my next article: My Ten Most Outrageous Experiences in Church.

~Andrew D. Sargent, PhD

[1] https://www.collezionegalleriaborghese.it/en/opere/david-with-the-head-of-goliath; Helen Langdon, Caravaggio: A Life (1998), p. 392.

[2] https://www.britannica.com/topic/The-Last-Judgment; Bernadine Barnes, Michelangelo and the Viewer in His Times (2017), p. 141.

[3] The Adoration of the Trinity (Landauer Altarpiece) (1511, Kunsthistorisches Museum, Vienna); Erwin Panofsky, The Life and Art of Albrecht Dürer (Princeton UP, 1943), p. 139.

[4] Jonathan Brown, El Greco of Toledo (1982), pp. 132–133.

[5] “Rembrandt’s only seascape depicts the moment when Christ calms the storm. One of the terrified disciples, grasping his cap at the center foreground, turns directly toward the viewer—traditionally identified as a self-portrait of the artist.” (Isabella Stewart Gardner Museum Collections Archive, “Rembrandt van Rijn, The Storm on the Sea of Galilee (1633).”

[6] Kenneth Clark, Rembrandt and the Italian Renaissance (1966), pp. 184–186.

[7] Gary Schwartz, Rembrandt: His Life, His Paintings (New York: Viking, 1985), pp. 114–116.

[8] J. Bruyn et al., A Corpus of Rembrandt Paintings, vol. 1 (1982), p. 23

[9] Gary Schwartz, Rembrandt: His Life, His Paintings (New York: Viking, 1985), pp. 292–293. Schwartz identifies this as “a deliberate self-presentation in the likeness of the Apostle Paul—aged, introspective, burdened with calling and revelation.”

[10] https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Christ_on_the_Mount_of_Olives_(Paul_Gauguin)

[11] Thomas Buser, “Gauguin’s Religion”, Art Journal 27, no. 4 (1968): 375-80; https://www.webexhibits.org/vangogh/letter/19/etc-Gauguin-1.htm?utm_source=chatgpt.com; J. Huret, Paul Gauguin devant ses tableaux, “L’Echo de Paris”, 23, 2, 1891.

[12] https://www.getty.edu/education/for_teachers/curricula/historical_witness/downloads/ensor_christ.pdf?utm_source=chatgpt.com; Carol Armstrong — Odd Man Out: Readings of the Work and Reputation of Edgar Degas (University of Chicago Press, 1991); Herwig Todts — James Ensor: Occasional Modernist — Ensor’s Artistic and Social Ideas and the Interpretation of His Art (Brepols).

[13] “The thorn necklace is her own crown of thorns: she shows herself calm and stoic in pain. The trickle of blood on her neck transforms private suffering into sanctified endurance.” (Hayden Herrera, Frida: A Biography of Frida Kahlo (1983), pp. 243–245); “In this painting Frida shows herself as both victim and saint. The thorn necklace, a parody of Christ’s crown of thorns, draws blood, and yet her expression is serene. Her pain is transfigured into something spiritual.” (Herrera, Frida. p. 244.); “Kahlo’s thorn necklace evokes Christ’s passion while re-gendering it: the artist’s wounded body becomes the new site of redemption.” Gannit Ankori, Imaging Her Selves: Frida Kahlo’s Poetics of Identity and Fragmentation (2002), p. 98; “For Frida, Christ’s wounds were metaphors for her own medical ordeal. Her pain became her art, and her art became her cross.” Tibol, Raquel, Frida Kahlo: An Open Life (1993), p. 212.

Discover more from Biblical Literacy with Dr. Andrew D. Sargent

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.